Myth: JavaScript needs classes

- [2012-03-17] I completely rewrote this post and changed its name (which previously was “JavaScript does not need classes”).

- [2012-07-29] Classes have been accepted for ECMAScript.next.

- [2012-10-03] Since this article has been written, it was decided that ECMAScript will have the special property __proto__ instead of the <| operator.

- [2013-10-21] Instead of the extension operator, ECMAScript.next will have the function Object.assign().

Prototypal inheritance is simple

In one way, JavaScript is clearly superior to most class-based languages – you can directly create objects: var jane = {

name: "Jane",

describe: function() {

return "Person called "+this.name;

}

};

console.log(jane.describe()); // Person called Jane

jane is an object which has been created via an object initializer. name and describe are properties. describe is a property whose value is a function. Such function-valued properties are called methods. An object initializer looks like a dictionary (map), but it is a real object. In most class-based languages, you need a class to create one. Hence the singleton pattern.

The core idea of prototypal inheritance is incredibly simple, simpler than classes. What makes JavaScript so complicated is that this core idea is obscured by trying to make the creation of instances (of a given type) look like Java. The core idea of prototypal inheritance is: an object can point to another object and thus make it its prototype. If a property isn’t found in the object, the search continues in the prototype (and, if it has one, its prototype, etc.). That allows one to model jane and tarzan as “instances” of PersonProto:

var PersonProto = {

describe: function () {

return "Person called "+this.name;

},

};

var jane = {

__proto__: PersonProto,

name: "Jane",

};

var tarzan = {

__proto__: PersonProto,

name: "Tarzan",

};

console.log(jane.describe()); // Person called Jane

jane and tarzan share the same prototype PersonProto which provides method describe() to both of them. Note how similar PersonProto is to a class.

Above, we have set up jane and tarzan manually, an exemplar is a factory for instances. In class-based languages, classes are exemplars. In JavaScript, the standard exemplars are constructors (functions). But one can also use objects as exemplars. The following sections explain both kinds of exemplars.

Instance factories: function exemplars

The default factory for instances of PersonProto is a constructor function (short: constructor). It is a normal function that is invoked via the new operator to produce an instance. In the following code, Person is a constructor. Person.prototype is the same object as PersonProto, it becomes the shared prototype of all instances of Person. Obviously, constructors correspond to classes in other languages. // Constructor: set up the instance

function Person(name) {

this.name = name;

}

// Prototype: shared by all instances

Person.prototype.describe = function () {

return "Person called "+this.name;

};

var jane = new Person("Jane");

console.log(jane instanceof Person); // true

console.log(jane.describe()); // Person called Jane

Subtyping and constructors

Things only become nasty once you come to subtyping a constructor, to creating a sub-constructor via inheritance. Let’s build Employee as a sub-constructor of Person: An employee is a person, but it additionally has a title and its describe() method works differently in that it also mentions the title. function Employee(name, title) {

Person.call(this, name);

this.title = title;

}

Employee.prototype = Object.create(Person.prototype);

Employee.prototype.constructor = Employee;

Employee.prototype.describe = function () {

return Person.prototype.describe.call(this)

+ " (" + this.title + ")";

};

var jane = new Employee("Jane", "CTO");

console.log(jane instanceof Person); // true

console.log(jane instanceof Employee); // true

console.log(jane.describe()); // Person called Jane (CTO)

There is no doubt that that is unwieldy (details are explained here). As a result, numerous libraries for handling inheritance have been written for JavaScript. But JavaScript needs a built-in solution. A minimal way of helping developers is to add language features that simplify the most common inheritance tasks. The next section describes four candidates.

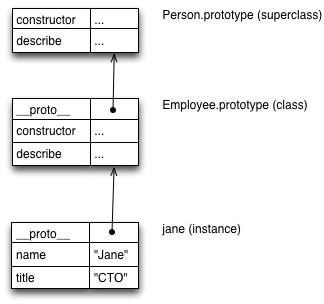

It is interesting to note that even with subtyping, instances still are easy to understand: The following is the structure of the instance jane.

|

| Person.prototype is the prototype of instances of Person, Employee.prototype is the prototype of instances of Employee (such as jane). By making Person.prototype the prototype of Employee.prototype, you let Employee inherit the methods of Person. |

Class-based languages have two relationships:

- instance-of is an inheritance relationship between an instance and a class. It lets the class provide the methods for the instance.

- subclass-of is an inheritance relationship between a subclass and a superclass. It lets the subclass inherit the superclass’s methods.

Improving constructors: minor language additions

If you add four minor constructs to JavaScript (as proposed for ECMAScript.next) then things become much easier:- The inheritance operator <| (read as “is extended by”):

var Super = function () { ... } var Sub = Super <| function () { ... }The constructor Sub extends the constructor Super. - Super property access:

super.describe()

- The extension operator .= adds properties to an object instead of replacing it:

var colorPoint = { color: "green" }; colorPoint .= { x: 33, y: 7 }Afterwards, colorPoint has the value{ color: "green", x: 33, y: 7 } - Shorter method syntax for object initializers:

{ method(arg1, arg2) { ... } }is an abbreviation for{ method: function (arg1, arg2) { ... } }

function Person(name) {

this.name = name;

}

Person.prototype .= {

describe() {

return "Person called "+this.name;

}

};

var Employee = Person <| function (name, title) {

super.constructor(name);

this.title = title;

}

Employee.prototype .= {

describe() {

return super.describe() + " (" + this.title + ")";

}

};

That looks much nicer, doesn’t it?

Instance factories: object exemplars

You can use the prototype (an object) as an exemplar. That is the core idea of object exemplars. They benefit from the language constructs that have been introduced in the previous section: var Person = {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

},

describe() {

return "Person called "+this.name;

}

};

var Employee = Person <| {

constructor(name, title) {

super.constructor(name);

this.title = title;

},

describe() {

return super.describe() + " (" + this.title + ")";

}

};

var jane = new Employee("Jane", "CTO");

console.log(jane instanceof Employee); // true

So we have flipped things: The previous prototypes Person.prototype and Employee.prototype are now the “classes” Person and Employee. And the previous constructor functions Person() and Employee() are now methods Person.constructor() and Employee.constructor(). Details are explained at [1].

For the above to work, you only need to adapt the following things:

- The inheritance operator <| must work for objects, too. Then it sets the prototype of an object.

- new must accept objects as operands, not just functions.

- instanceof must allow objects as its right-hand side, not just functions.

- super works the same for function exemplars and object exemplars: It looks for the super-property starting in the prototype of where the current method is located.

Constructor1 <| Constructor2

Prototype1 <| Prototype2

Constructor <| Prototype

Prototype <| Constructor

Advantage. The main advantage of object exemplars is that they are a good fit for prototypal inheritance, because you can work directly with prototypes. In contrast, with constructors, there is always an indirection after the creation of an instance: You now always need the constructor to access the prototype. The following examples demonstrate this difference between function exemplars and object exemplars:

- Checking for an instance-of relationship:

Func. ex.: o instanceof E === E.prototype.isPrototypeOf(o) Obj. ex.: o instanceof E === E.isPrototypeOf(o) - Extending an exemplar:

Func. ex.: Sub.prototype = Object.create(Super.prototype) Obj. ex.: Sub = Object.create(Super) - Checking for a superclass-of relationship:

Func. ex.: Super.prototype .isPrototypeOf(Sub.prototype) Obj. ex.: Super .isPrototypeOf(Sub) - Generic methods:

Func. ex.: Array.prototype.slice.call(arguments) Obj. ex.: Array.slice.call(arguments)

Syntactic sugar for exemplars: class declarations

The minor language additions presented above do help, but are still challenging for JavaScript newbies, especially those coming from class-based programming languages. One step further is to provide syntactic sugar for exemplars. Then there is a dedicated syntactic construct for exemplars instead of functions or objects pulling double-duty. The sugar is called “class declaration”, but it doesn’t change the fundamental (elegant) nature of JavaScript’s prototypal inheritance. Class declarations are not real classes, as used by languages such as C++, Java or C#. The syntax for class declarations is currently being worked on. It might look something like this: class Person {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

},

describe() {

return "Person called "+this.name;

}

}

class Employee extends Person {

constructor(name, title) {

super.constructor(name);

this.title = title;

},

describe() {

return super.describe() + " (" + this.title + ")";

}

}

JavaScript has a long history of proposals for class-like syntactic constructs. The proposal that might be added to ECMAScript.next is called “Maximally Minimal Classes”. But it is still hotly debated.

Advantages of class declarations:

- Prevent certain anti-patterns: such as non-method properties in prototypes.

- Easier to detect by IDEs: Simply having a single standard way of doing inheritance (as opposed to numerous APIs) will be a boon in this department.

- Beginner-friendly: Class declarations are a dedicated construct for exemplars that is easy to understand by beginners.

Desugar to function exemplars or to object exemplars?

The main issue is whether class declarations are syntactic sugar for function exemplars or for object exemplars. Breaking compatibility is probably not an option, so the former approach will be taken. Note, however, that the conceptual disconnect between class declarations and function exemplars is much larger than between class declarations and object exemplars. Hence, desugaring a class declaration to a function exemplar means that much more “magic” (not the good kind...) needs to happen under the hood. For example, if you examine a desugared class, you will be surprised that it is the constructor method which has a property called prototype with an object where all your methods have been moved.Conclusion

This post argued that JavaScript’s prototypal inheritance is dead simple at its core. It is only made complicated by JavaScript’s default instance factories, constructors. There are two ways of reducing the complexity of constructors:- Make it easier to work with constructors: As we have seen, only a few new language features can make a large difference.

- Introduce object exemplars: use prototypes as classes.

Related reading

- Prototypes as classes – an introduction to JavaScript inheritance [explains object exemplars in detail, under their former name “prototypes as classes”; includes a library for ECMAScript 5]

- ECMAScript.next: the “TXJS” update by Eich [an overview of what’s currently planned for ECMAScript.next a.k.a. ECMAScript 6]