ECMAScript 6 promises (1/2): foundations

This blog post is outdated. Please read chapter “Asynchronous programming (background)” in “Exploring ES6”.

This blog post explains foundations of asynchronous programming in JavaScript. It is first in a series of two posts and prepares you for part two, which covers promises and the ECMAScript 6 promise API.

The JavaScript call stack

When a function f calls a function g, g needs to know where to return to (inside f) after it is done. This information is usually managed with a stack, the call stack. Let’s look at an example.

function h(z) {

// Print stack trace

console.log(new Error().stack); // (A)

}

function g(y) {

h(y + 1); // (B)

}

function f(x) {

g(x + 1); // (C)

}

f(3); // (D)

return; // (E)

Initially, when the program above is started, the call stack is empty. After the function call f(3) in line (D), the stack has one entry:

- Location in global scope

After the function call g(x + 1) in line (C), the stack has two entries:

- Location in

f - Location in global scope

After the function call h(y + 1) in line (B), the stack has three entries:

- Location in

g - Location in

f - Location in global scope

The stack trace printed in line (A) shows you what the call stack looks like:

Error

at h (stack_trace.js:2:17)

at g (stack_trace.js:6:5)

at f (stack_trace.js:9:5)

at <global> (stack_trace.js:11:1)

Next, each of the functions terminates and each time the top entry is removed from the stack. After function f is done, we are back in global scope and the call stack is empty. In line (E) we return and the stack is empty, which means that the program terminates.

The browser event loop

Simplifyingly, each browser tab runs (in) a single process: the event loop. This loop executes browser-related things (so-called tasks) that it is fed via a task queue. Examples of tasks are:

- Parsing HTML

- Executing JavaScript code in script elements

- Reacting to user input (mouse clicks, key presses, etc.)

- Processing the result of an asynchronous network request

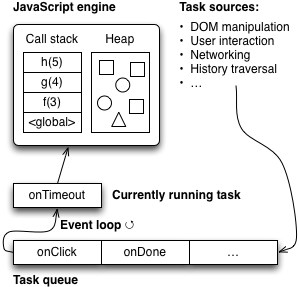

Items 2–4 are tasks that run JavaScript code, via the engine built into the browser. They terminate when the code terminates. Then the next task from the queue can be executed. The following diagram (inspired by a slide by Philip Roberts [1]) gives an overview of how all these mechanisms are connected.

The event loop is surrounded by other processes running in parallel to it (timers, input handling, etc.). These processes communicate with it by adding tasks to its queue.

Timers

Browsers have timers. setTimeout() creates a timer, waits until it fires and then adds a task to the queue. It has the signature:

setTimeout(callback, ms)

After ms milliseconds, callback is added to the task queue. It is important to note that ms only specifies when the callback is added, not when it actually executed. That may happen much later, especially if the event loop is blocked (as demonstrated later in this post).

setTimeout() with ms set to zero is a commonly used work-around to add something to the task queue right away. However, some browsers do not allow ms to be below a minimum (4 ms in Firefox); they set it to that minimum if it is.

Displaying DOM changes

For most DOM changes (especially those involving a re-layout), the display isn’t updated right away. “Layout happens off a refresh tick every 16ms” (@bz_moz) and must be given a chance to run via the event loop.

There are ways to coordinate frequent DOM updates with the browser, to avoid clashing with its layout rhythm. Consult the documentation on requestAnimationFrame() for details.

Run-to-completion semantics

JavaScript has so-called run-to-completion semantics: The current task is always finished before the next task is executed. That means that each task has complete control over all current state and doesn’t have to worry about concurrent modification.

Let’s look at an example:

setTimeout(function () { // (A)

console.log('Second');

}, 0);

console.log('First'); // (B)

The function starting in line (A) is added to the task queue immediately, but only executed after the current piece of code is done (in particular line (B)!). That means that this code’s output will always be:

First

Second

Blocking the event loop

As we have seen, each tab (in some browers, the complete browser) is managed by a single process – both the user interface and all other computations. That means that you can freeze the user interface by performing a long-running computation in that process. The following code demonstrates that. You can try it out online.

<a id="block" href="">Block for 5 seconds</a>

<p>

<button>Simple button</button>

<script>

...

function onClick(event) {

event.preventDefault();

console.log('Blocking...');

sleep(5000);

console.log('Done');

}

function sleep(milliseconds) {

var start = Date.now();

while ((Date.now() - start) < milliseconds);

}

</script>

Whenever the link at the beginning is clicked, the function onClick() is triggered. It uses the – synchronous – sleep() function to block the event loop for five seconds. During those seconds, the user interface doesn’t work. For example, you can’t click the “Simple button”.

Avoiding blocking

You avoid blocking the event loop in two ways:

First, you don’t perform long-running computations in the main process, you move them to a different process. This can be achieved via the Worker API.

Second, you don’t (synchronously) wait for the results of a long-running computation (your own algorithm in a Worker process, a network request, etc.), you carry on with the event loop and let the computation notify you when it is finished. In fact, you usually don’t even have a choice in browsers and have to do things this way. For example, there is no built-in way to sleep synchronously (like the previously implemented sleep()). Instead, setTimeout() lets you sleep asynchronously.

The next section explains techniques for waiting asynchronously for results.

Receiving results asynchronously

Two common patterns for receiving results asynchronously are: events and callbacks.

Asynchronous results via events

In this pattern for asynchronously receiving results, you create an object for each request and register event handlers with it: one for a successful computation, another one for handling errors. The following code shows how that works with the XMLHttpRequest API:

var req = new XMLHttpRequest();

req.open('GET', url);

req.onload = function() {

if (req.status == 200) {

processData(req.response);

} else {

console.log('ERROR', req.statusText);

}

};

req.onerror = function() {

console.log('Network Error');

};

req.send(); // Add request to task queue

Note that the last line doesn’t actually perform the request, it adds it to the task queue. Therefore, you could also call that method right after open(), before setting up onload and onerror. Things would work the same, due to JavaScript’s run-to-completion semantics.

If you are used to multi-threaded programming languages, IndexedDB requests look like they might be prone to race conditions. However, run to completion makes the following code safe in JavaScript:

var openRequest = indexedDB.open('test', 1);

openRequest.onsuccess = function(event) {

console.log('Success!');

var db = event.target.result;

};

openRequest.onerror = function(error) {

console.log(error);

};

open() does not immediately open the database, it adds a task to the queue, which is executed after the current task is finished. That is why you can (and in fact must) register event handlers after calling open().

Asynchronous results via callbacks

If you handle asynchronous results via callbacks, you pass callback functions as trailing parameters to asynchronous function or method calls.

The following is an example in Node.js. We read the contents of a text file via an asynchronous call to fs.readFile():

// Node.js

fs.readFile('myfile.txt', { encoding: 'utf8' },

function (error, text) { // (A)

if (error) {

// ...

}

console.log(text);

});

If readFile() is successful, the callback in line (A) receives a result via the parameter text. If it isn’t, the callback gets an error (often an instance of Error or a sub-constructor) via its first parameter.

The same code in classic functional programming style would look like this:

// Functional

readFileFunctional('myfile.txt', { encoding: 'utf8' },

function (text) { // success

console.log(text);

},

function (error) { // failure

// ...

});

Continuation-passing style

The programming style of using callbacks (especially in the functional manner shown previously) is also called continuation-passing style (CPS), because the next step (the continuation) is explicitly passed as a parameter. This gives an invoked function more control over what happens next and when.

The following code illustrates CPS:

console.log('A');

identity('B', function step2(result2) {

console.log(result2);

identity('C', function step3(result3) {

console.log(result3);

});

console.log('D');

});

console.log('E');

// Output: A E B D C

function identity(input, callback) {

setTimeout(function () {

callback(input);

}, 0);

}

For each step, the control flow of the program continues inside the callback. This leads to nested functions, which are sometimes referred to as callback hell. However, you can often avoid nesting, because JavaScript’s function declarations are hoisted (their definitions are evaluated at the beginning of their scope). That means that you can call ahead and invoke functions defined later in the program. The following code uses hoisting to flatten the previous example.

console.log('A');

identity('B', step2);

function step2(result2) {

// The program continues here

console.log(result2);

identity('C', step3);

console.log('D');

}

function step3(result3) {

console.log(result3);

}

console.log('E');

[2] contains more information on CPS.

Composing code in CPS

In normal JavaScript style, you compose pieces of code via:

- Putting them one after another. This is blindingly obvious, but it’s good to remind ourselves that concatenating code in normal style is sequential composition.

- Array methods such as

map(),filter()andforEach() - Loops such as

forandwhile

The library Async.js provides combinators to let you do similar things in CPS, with Node.js-style callbacks. It is used in the following example to load the contents of three files, whose names are stored in an array.

var async = require('async');

var fileNames = [ 'foo.txt', 'bar.txt', 'baz.txt' ];

async.map(fileNames,

function (fileName, callback) {

fs.readFile(fileName, { encoding: 'utf8' }, callback);

},

// Process the result

function (error, textArray) {

if (error) {

console.log(error);

return;

}

console.log('TEXTS:\n' + textArray.join('\n----\n'));

});

Pros and cons of callbacks

Using callbacks results in a radically different programming style, CPS. The main advantage of CPS is that its basic mechanisms are easy to understand. However, it has disadvantages:

-

Error handling becomes more complicated: There are now two ways in which errors are reported – via callbacks and via exceptions. You have to be careful to combine both properly.

-

Less elegant signatures: In synchronous functions, there is a clear separation of concerns between input (parameters) and output (function result). In asynchronous functions that use callbacks, these concerns are mixed: the function result doesn’t matter and some parameters are used for input, others for output.

-

Composition is more complicated: Because the concern “output” shows up in the parameters, it is more complicated to compose code via combinators.

Callbacks in Node.js style have three disadvantages (compared to those in a functional style):

- The

ifstatement for error handling adds verbosity. - Reusing error handlers is harder.

- Providing a default error handler is also harder. A default error handler is useful if you make a function call and don’t want to write your own handler. It could also be used by a function if a caller doesn’t specify a handler.

Looking ahead

The second part of this series covers promises and the ECMAScript 6 promise API. Promises are more complicated under the hood than callbacks. In exchange, they bring several significant advantages.

Further reading

Reviewers

I’d like to thank the following people for reviewing this post.

“Help, I'm stuck in an event-loop” by Philip Roberts (video). ↩︎

Asynchronous programming and continuation-passing style in JavaScript ↩︎