Tail call optimization in ECMAScript 6

Update 2018-05-09: Even though tail call optimization is part of the language specification, it isn’t supported by many engines and that may never change. The ideas are still interesting, however and explained in this blog post.

ECMAScript 6 offers tail call optimization, where you can make some function calls without growing the call stack. This blog post explains how that works and what benefits it brings.

What is tail call optimization?

To understand what tail call optimization (TCO) is, we will examine the following piece of code. I’ll first explain how it is executed without TCO and then with TCO.

function id(x) {

return x; // (A)

}

function f(a) {

let b = a + 1;

return id(b); // (B)

}

console.log(f(2)); // (C)

Normal execution

Let’s assume there is a JavaScript engine that manages function calls by storing local variables and return addresses on a stack. How would such an engine execute the code?

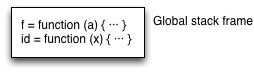

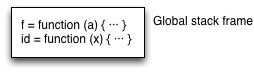

Step 1. Initially, there are only the global variables id and f on the stack.

The block of stack entries encodes the state (local variables, including parameters) of the current scope and is called a stack frame.

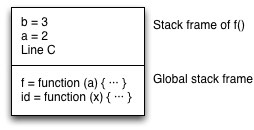

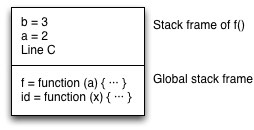

Step 2. In line C, f() is called: First, the location to return to is saved on the stack. Then f’s parameters are allocated and execution jumps to its body. The stack now looks as follows.

There are now two frames on the stack: One for the global scope (bottom) and one for f() (top). f’s stack frame includes the return address, line C.

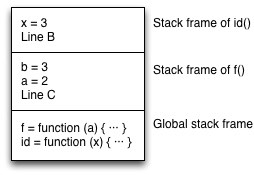

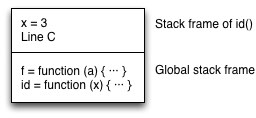

Step 3. id() is called in line B. Again, a stack frame is created that contains the return address and id’s parameter.

Step 4. In line A, the result x is returned. id’s stack frame is removed and execution jumps to the return address, line B. (There are several ways in which returning a value could be handled. Two common solutions are to leave the result on a stack or to hand it over in a register. I ignore this part of execution here.)

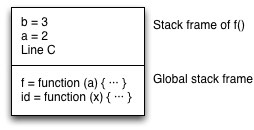

The stack now looks as follows:

Step 5. In line B, the value that was returned by id is returned to f’s caller. Again, the topmost stack frame is removed and execution jumps to the return address, line C.

Step 6. Line C receives the value 3 and logs it.

Tail call optimization

function id(x) {

return x; // (A)

}

function f(a) {

let b = a + 1;

return id(b); // (B)

}

console.log(f(2)); // (C)

If you look at the previous section then there is one step that is unnecessary – step 5. All that happens in line B is that the value returned by id() is passed on to line C. Ideally, id() could do that itself and the intermediate step could be skipped.

We can make this happen by implementing the function call in line B differently. Before the call happens, the stack looks as follows.

If we examine the call we see that it is the very last action in f(). Once id() is done, the only remaining action performed by f() is to pass id’s result to f’s caller. Therefore, f’s variables are not needed, anymore and its stack frame can be removed before making the call. The return address given to id() is f’s return address, line C. During the execution of id(), the stack looks like this:

Then id() returns the value 3. You could say that it returns that value for f(), because it transports it to f’s caller, line C.

Let’s review: The function call in line B is a tail call. Such a call can be done with zero stack growth. To find out whether a function call is a tail call, we must check whether it is in a tail position (i.e., the last action in a function). How that is done is explained in the next section.

Checking whether a function call is in a tail position

We have just learned that tail calls are function calls that can be executed more efficiently. But what counts as a tail call?

First, the way in which you call a function does not matter. The following calls can all be optimized if they appear in a tail position:

- Function call:

func(···) - Dispatched method call:

obj.method(···) - Direct method call via

call():func.call(···) - Direct method call via

apply():func.apply(···)

Tail calls in expressions

Arrow functions can have expressions as bodies. For tail call optimization, we therefore have to figure out where function calls are in tail positions in expressions. Only the following expressions can contain tail calls:

- The conditional operator (

? :) - The logical Or operator (

||) - The logical And operator (

&&) - The comma operator (

,)

Let’s look at an example for each one of them.

The conditional operator (? :)

const a = x => x ? f() : g();

Both f() and g() are in tail position.

The logical Or operator (||)

const a = () => f() || g();

f() is not in a tail position, but g() is in a tail position. To see why, take a look at the following code, which is equivalent to the previous code:

const a = () => {

let fResult = f(); // not a tail call

if (fResult) {

return fResult;

} else {

return g(); // tail call

}

};

The result of the logical Or operator depends on the result of f(), which is why that function call is not in a tail position (the caller does something with it other than returning it). However, g() is in a tail position.

The logical And operator

const a = () => f() && g();

f() is not in a tail position, but g() is in a tail position. To see why, take a look at the following code, which is equivalent to the previous code:

const a = () => {

let fResult = f(); // not a tail call

if (!fResult) {

return fResult;

} else {

return g(); // tail call

}

};

The result of the logical And operator depends on the result of f(), which is why that function call is not in a tail position (the caller does something with it other than returning it). However, g() is in a tail position.

The comma operator (,)

const a = () => (f() , g());

f() is not in a tail position, but g() is in a tail position. To see why, take a look at the following code, which is equivalent to the previous code:

const a = () => {

f();

return g();

}

Tail calls in statements

For statements, the following rules apply.

Only these compound statements can contain tail calls:

- Blocks (as delimited by

{}, with or without a label) if: in either the “then” clause or the “else” clause.do-while,while,for: in their bodies.switch: in its body.try-catch: only in thecatchclause. Thetryclause has thecatchclause as a context that can’t be optimized away.try-finally,try-catch-finally: only in thefinallyclause, which is a context of the other clauses that can’t be optimized away.

Of all the atomic (non-compound) statements, only return can contain a tail call. All other statements have context that can’t be optimized away. The following statement contains a tail call if expr contains a tail call.

return «expr»;

Tail call optimization can only be made in strict mode

In non-strict mode, most engines have the following two properties that allow you to examine the call stack:

func.arguments: contains the arguments of the most recent invocation offunc.func.caller: refers to the function that most recently calledfunc.

With tail call optimization, these properties don’t work, because the information that they rely on may have been removed. Therefore, strict mode forbids these properties (as described in the language specification) and tail call optimization only works in strict mode.

Pitfall: solo function calls are never in tail position

The function call bar() in the following code is not in tail position:

function foo() {

bar(); // this is not a tail call in JS

}

The reason is that the last action of foo() is not the function call bar(), it is (implicitly) returning undefined. In other words, foo() behaves like this:

function foo() {

bar();

return undefined;

}

Callers can rely on foo() always returning undefined. If bar() were to return a result for foo(), due to tail call optimization, then that would change foo’s behavior.

Therefore, if we want bar() to be a tail call, we have to change foo() as follows.

function foo() {

return bar(); // tail call

}

Tail-recursive functions

A function is tail-recursive if the main recursive calls it makes are in tail positions.

For example, the following function is not tail recursive, because the main recursive call in line A is not in a tail position:

function factorial(x) {

if (x <= 0) {

return 1;

} else {

return x * factorial(x-1); // (A)

}

}

factorial() can be implemented via a tail-recursive helper function facRec(). The main recursive call in line A is in a tail position.

function factorial(n) {

return facRec(n, 1);

}

function facRec(x, acc) {

if (x <= 1) {

return acc;

} else {

return facRec(x-1, x*acc); // (A)

}

}

That is, some non-tail-recursive functions can be transformed into tail-recursive functions.

Tail-recursive loops

Tail call optimization makes it possible to implement loops via recursion without growing the stack. The following are two examples.

forEach()

function forEach(arr, callback, start = 0) {

if (0 <= start && start < arr.length) {

callback(arr[start], start, arr);

return forEach(arr, callback, start+1); // tail call

}

}

forEach(['a', 'b'], (elem, i) => console.log(`${i}. ${elem}`));

// Output:

// 0. a

// 1. b

findIndex()

function findIndex(arr, predicate, start = 0) {

if (0 <= start && start < arr.length) {

if (predicate(arr[start])) {

return start;

}

return findIndex(arr, predicate, start+1); // tail call

}

}

findIndex(['a', 'b'], x => x === 'b'); // 1